Organization

Al-Qaeda's management philosophy has been described as "centralization of decision and decentralization of execution."[17] Following the War on Terrorism, it is thought that al-Qaeda's leadership has "become geographically isolated", leading to the "emergence of decentralized leadership" of regional groups using the al-Qaeda "brand name".[18][19]

Many terrorism experts do not believe that the global jihadist movement is driven at every level by bin Laden and his followers. Although bin Laden still had huge ideological sway over some Muslim extremists, experts argue that al-Qaeda has fragmented over the years into a variety of disconnected regional movements that have little connection with each other. Marc Sageman, a psychiatrist and former CIA officer, said that Al-Qaeda would now just be a "loose label for a movement that seems to target the West". "There is no umbrella organisation. We like to create a mythical entity called [al-Qaeda] in our minds, but that is not the reality we are dealing with."[20]

Others, however, see Al-Qaeda as an integrated network that is strongly led from the Pakistani tribal areas and has a powerful strategic purpose. Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert atGeorgetown University, said "It amazes me that people don't think there is a clear adversary out there, and that our adversary does not have a strategic approach."[20]

Al-Qaeda has the following direct franchises:

Leadership

Information mostly acquired from Jamal al-Fadl provided American authorities with a rough picture of how the group was organized. While the veracity of the information provided by al-Fadl and the motivation for his cooperation are both disputed, American authorities base much of their current knowledge of al-Qaeda on his testimony.[21]

Before his death Osama bin Laden was the emir, or commander, and was the Senior Operations Chief of al-Qaeda[citation needed] (though originally this role may have been filled by Abu Ayoub al-Iraqi).

As of August 6, 2010, the chief of operations was considered to be Adnan Gulshair el Shukrijumah, replacing Khalid Sheikh Mohammed.[22]

Bin Laden was advised by a Shura Council, which consists of senior al-Qaeda members, estimated by Western officials at about 20–30 people. Ayman al-Zawahiri is al-Qaeda's Deputy Operations Chief; Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was the senior leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, but his safehouse was hit by U.S. missiles in a targeted killing, and Abu Ayyub al-Masri may have succeeded him.

Al-Qaeda's network was built from scratch as a conspiratorial network that draws on leaders of all its regional nodes "as and when necessary to serve as an integral part of its high command."[23]

- The Military Committee is responsible for training operatives, acquiring weapons, and planning attacks.

- The Money/Business Committee funds the recruitment and training of operatives through the hawala banking system. U.S-led efforts to eradicate the sources of terrorist financing[24]were most successful in the year immediately following September 11;[25] al-Qaeda continues to operate through unregulated banks, such as the 1,000 or so hawaladars in Pakistan, some of which can handle deals of up to $10 million.[26] It also provides air tickets and false passports, pays al-Qaeda members, and oversees profit-driven businesses.[27] In The 9/11 Commission Report, it was estimated that al-Qaeda required $30 million-per-year to conduct its operations.

- The Law Committee reviews Islamic law, and decides whether particular courses of action conform to the law.

- The Islamic Study/Fatwah Committee issues religious edicts, such as an edict in 1998 telling Muslims to kill Americans.

- In the late 1990s there was a publicly known Media Committee, which ran the now-defunct newspaper Nashrat al Akhbar (Newscast) and handled public relations.

- In 2005, al-Qaeda formed As-Sahab, a media production house, to supply its video and audio materials.

Command structure

When asked about the possibility of Al-Qaeda's connection to the 7 July 2005 London bombings in 2005, Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Ian Blair said: "Al-Qaeda is not an organization. Al-Qaeda is a way of working ... but this has the hallmark of that approach ... Al-Qaeda clearly has the ability to provide training ... to provide expertise ... and I think that is what has occurred here."[28]

However, on August 13, 2005, The Independent newspaper, quoting police and MI5 investigations, reported that the 7 July bombers acted independently of an al-Qaeda terror mastermind someplace abroad.[29]

What exactly al-Qaeda is, or was, remains in dispute. Author and journalist Adam Curtis contends that the idea of al-Qaeda as a formal organization is primarily an American invention. Curtis contends the name "al-Qaeda" was first brought to the attention of the public in the 2001 trial of bin Laden and the four men accused of the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in East Africa:

The reality was that bin Laden and Ayman Zawahiri had become the focus of a loose association of disillusioned Islamist militants who were attracted by the new strategy. But there was no organization. These were militants who mostly planned their own operations and looked to bin Laden for funding and assistance. He was not their commander. There is also no evidence that bin Laden used the term "al-Qaeda" to refer to the name of a group until after September the 11th, when he realized that this was the term the Americans had given it.[30]

As a matter of law, the U.S. Department of Justice needed to show that bin Laden was the leader of a criminal organization in order to charge him in absentia under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, also known as the RICO statutes. The name of the organization and details of its structure were provided in the testimony of Jamal al-Fadl, who said he was a founding member of the organization and a former employee of bin Laden.[31] Questions about the reliability of al-Fadl's testimony have been raised by a number of sources because of his history of dishonesty, and because he was delivering it as part of a plea bargain agreement after being convicted of conspiring to attack U.S. military establishments.[21][32] Sam Schmidt, one of his defense lawyers, said:

There were selective portions of al-Fadl's testimony that I believe was false, to help support the picture that he helped the Americans join together. I think he lied in a number of specific testimony about a unified image of what this organization was. It made al-Qaeda the new Mafia or the new Communists. It made them identifiable as a group and therefore made it easier to prosecute any person associated with al-Qaeda for any acts or statements made by bin Laden.[30]

Field operatives

The number of individuals in the organization who have undergone proper military training, and are capable of commanding insurgent forces, is largely unknown. In 2006, it was estimated that al-Qaeda had several thousand commanders embedded in 40 different countries.[33] As of 2009, it was believed that no more than 200–300 members were still active commanders.[34]

According to the award-winning 2004 BBC documentary The Power of Nightmares, al-Qaeda was so weakly linked together that it was hard to say it existed apart from bin Laden and a small clique of close associates. The lack of any significant numbers of convicted al-Qaeda members, despite a large number of arrests on terrorism charges, was cited by the documentary as a reason to doubt whether a widespread entity that met the description of al-Qaeda existed.[35]

Insurgent forces

According to Robert Cassidy, al-Qaeda controls two separate forces deployed alongside insurgents in Iraq and Pakistan. The first, numbering in the tens of thousands, was "organized, trained, and equipped as insurgent combat forces" in the Soviet-Afghan war.[33] It was made up primarily of foreign mujahideen from Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Many went on to fight in Bosnia and Somalia for global jihad. Another group, approximately 10,000 strong, live in Western states and have received rudimentary combat training.[33]

Other analysts have described al-Qaeda's rank and file as changing from being "predominantly Arab," in its first years of operation, to "largely Pakistani," as of 2007.[36] It has been estimated that 62% of al-Qaeda members have university education.[37]

Strategy

On March 11, 2005, Al-Quds Al-Arabi published extracts from Saif al-Adel's document "Al Quaeda's Strategy to the Year 2020".[38][39] Abdel Bari Atwan summarizes this strategy as comprising five stages:

- Provoke the United States into invading a Muslim country.

- Incite local resistance to occupying forces.

- Expand the conflict to neighboring countries, and engage the U.S. in a long war of attrition.

- Convert Al-Qaeda into an ideology and set of operating principles that can be loosely franchised in other countries without requiring direct command and control, and via these franchises incite attacks against countries allied with the U.S. until they withdraw from the conflict, as happened with the 2004 Madrid train bombings, but which did not have the same effect with the 7 July 2005 London bombings.

- The U.S. economy will finally collapse under the strain of too many engagements in too many places, similarly to the Soviet war in Afghanistan, Arab regimes supported by the U.S. will collapse, and a Wahhabi Caliphate will be installed across the region.

Etymology

In Arabic, al-Qaeda has four syllables (Arabic pronunciation: [ælˈqɑːʕɪdɐ]). However, since two of the Arabic consonants in the name (the voiceless uvular plosive [q] and the voiced pharyngeal fricative [ʕ]) are not phones found in the English language, the closest naturalized English pronunciations include /ælˈkaɪdə/, /ælˈkeɪdə/ and /ˌælkɑːˈiːdə/.[citation needed] Al-Qaeda's name can also be transliterated as al-Qaida, al-Qa'ida, el-Qaida, or al-Qaeda.[40]

The name comes from the Arabic noun qā'idah, which means foundation or basis, and can also refer to a military base. The initial al- is the Arabic definite article the, hence the base.[41]

Bin Laden explained the origin of the term in a videotaped interview with Al Jazeera journalist Tayseer Alouni in October 2001:

The name 'al-Qaeda' was established a long time ago by mere chance. The late Abu Ebeida El-Banashiri established the training camps for our mujahedeen against Russia's terrorism. We used to call the training camp al-Qaeda. The name stayed.[42]

It has been argued that two documents seized from the Sarajevo office of the Benevolence International Foundation prove that the name was not simply adopted by the mujahid movement and that a group called al-Qaeda was established in August 1988. Both of these documents contain minutes of meetings held to establish a new military group, and contain the term "al-qaeda".[43]

Former British Foreign Secretary Robin Cook wrote that the word Al-Qaeda should be translated as "the database", and originally referred to the computer file of the thousands ofmujahideen militants who were recruited and trained with CIA help to defeat the Russians.[44] In April 2002, the group assumed the name Qa'idat al-Jihad, which means "the base of Jihad". According to Diaa Rashwan, this was "apparently as a result of the merger of the overseas branch of Egypt's al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamist Jihad, or EIJ) group, led by Ayman El-Zawahiri, with the groups Bin Laden brought under his control after his return to Afghanistan in the mid-1990s."[45]

Ideology

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Islamism |

|---|

|

Politics portal |

The radical Islamist movement in general and al-Qaeda in particular developed during the Islamic revival and Islamist movement of the last three decades of the 20th century, along with less extreme movements.

Some have argued that "without the writings" of Islamic author and thinker Sayyid Qutb, "al-Qaeda would not have existed."[46] Qutb preached that because of the lack of sharia law, the Muslim world was no longer Muslim, having reverted to pre-Islamic ignorance known as jahiliyyah.

To restore Islam, he said a vanguard movement of righteous Muslims was needed to establish "true Islamic states", implement sharia, and rid the Muslim world of any non-Muslim influences, such as concepts like socialism and nationalism. Enemies of Islam in Qutb's view included "treacherous Orientalists"[47] and "world Jewry", who plotted "conspiracies" and "wicked[ly]" opposed Islam.

In the words of Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, a close college friend of bin Laden:

Islam is different from any other religion; it's a way of life. We [Khalifa and bin Laden] were trying to understand what Islam has to say about how we eat, who we marry, how we talk. We read Sayyid Qutb. He was the one who most affected our generation.[48]

Qutb had an even greater influence on bin Laden's mentor and another leading member of al-Qaeda,[49] Ayman al-Zawahiri. Zawahiri's uncle and maternal family patriarch, Mafouz Azzam, was Qutb's student, then protégé, then personal lawyer, and finally executor of his estate—one of the last people to see Qutb before his execution. "Young Ayman al-Zawahiri heard again and again from his beloved uncle Mahfouz about the purity of Qutb's character and the torment he had endured in prison."[50] Zawahiri paid homage to Qutb in his work Knights under the Prophet's Banner.[51]

One of the most powerful of Qutb's ideas was that many who said they were Muslims were not. Rather, they were apostates. That not only gave jihadists "a legal loophole around the prohibition of killing another Muslim," but made "it a religious obligation to execute" these self-professed Muslims. These alleged apostates included leaders of Muslim countries, since they failed to enforce sharia law.[52]

The fatwa on terrorism is regarded as a direct assault on the ideology of Al-Qaeda which dismantles it from the sources of Quran and sunnah.[53]

Religious compatibility

Abdel Bari Atwan writes that:

While the leadership's own theological platform is essentially Salafi, the organization's umbrella is sufficiently wide to encompass various schools of thought and political leanings. Al-Qaeda counts among its members and supporters people associated with Wahhabism, Shafi'ism, Malikism, and Hanafism. There are even some whose beliefs and practices are directly at odds with Salafism, such as Yunis Khalis, one of the leaders of the Afghan mujahedin. He is a mystic who visits tombs of saints and seeks their blessings—practices inimical to bin Laden's Wahhabi-Salafi school of thought. The only exception to this pan-Islamic policy is Shi'ism. Al-Qaeda seems implacably opposed to it, as it holds Shi'ism to be heresy. In Iraq it has openly declared war on the Badr Brigades, who have fully cooperated with the US, and now considers even Shi'i civilians to be legitimate targets for acts of violence.[54]

History

Researchers have described five distinct phases in the development of al-Qaeda: the beginning in the late 1980s, the "wilderness" period in 1990–96, its "heyday" in 1996–2001, the network period of 2001–05, and a period of fragmentation from 2005 to today.[55]

Jihad in Afghanistan

The origins of al-Qaeda as a network inspiring terrorism around the world and training operatives can be traced to the Soviet War in Afghanistan (December 1979 – February 1989).[56] The U.S. viewed the conflict in Afghanistan, with the Afghan Marxists and allied Soviet troops on one side and the native Afghan mujahideen radical Islamic militants on the other, as a blatant case of Soviet expansionism and aggression. The U.S. channeled funds through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency to the Afghan Mujahideen fighting the Soviet occupation in a CIA program called Operation Cyclone.[57][58]

At the same time, a growing number of Arab mujahideen joined the jihad against the Afghan Marxist regime, facilitated by international Muslim organizations, particularly the Maktab al-Khidamat,[59] whose funds came from some of the $600 million a year donated to thejihad by the Saudi Arabia government and individual Muslims—particularly independent Saudi businessmen who were approached by bin Laden.[60][page needed]

Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), or the "Services Office", a Muslim organization founded in 1980 to raise and channel funds and recruit foreignmujahideen for the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, was established by Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, a Palestinian Islamic scholar and member of the Muslim Brotherhood, and Bin Laden in Peshawar, Pakistan, in 1984.

From 1986, it began to set up a network of recruiting offices in the U.S., the hub of which was the Al Kifah Refugee Center at the Farouq Mosque inBrooklyn's Atlantic Avenue. Among notable figures at the Brooklyn center were "double agent" Ali Mohamed, whom FBI special agent Jack Cloonan called "bin Laden's first trainer,"[61] and "Blind Sheikh" Omar Abdel-Rahman, a leading recruiter of mujahideen for Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda evolved from the MAK.

MAK organized guest houses in Peshawar, near the Afghan border, and gathered supplies for the construction of paramilitary training camps to prepare foreign recruits for the Afghan war front. Azzam persuaded Bin Laden to join MAK.[when?] Bin Laden became a "major financier" of the mujahideen, spending his own money and using his connections with "the Saudi royal family and the petro-billionaires of the Gulf" in order to improve public opinion of the war and raise more funds.[62] Beginning in 1987, Azzam and bin Laden started creating camps inside Afghanistan.[63]

U.S. government financial support for the Afghan Islamic militants was substantial. Aid to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, an Afghan mujahideen leader. and founder and leader of the Hezb-e Islami radical Islamic militant faction, alone amounted "by the most conservative estimates" to $600 million. Hekmatyar "worked closely" with bin Laden in the early 1990s.[64] In addition to hundreds of millions of dollars of American aid, Hekmatyar also received the lion's share of aid from the Saudis.[65] There is evidence that the CIA supported Hekmatyar's drug trade activities by giving him immunity for his opium trafficking that financed operation of his militant faction.[66]

The MAK and foreign mujahideen volunteers, or "Afghan Arabs," did not play a major role in the war. While over 250,000 Afghan mujahideen fought the Soviets and the communist Afghan government, it is estimated that were never more than 2,000 foreign mujahideen in the field at any one time.[67]Nonetheless, foreign mujahideen volunteers came from 43 countries, and the total number that participated in the Afghan movement between 1982 and 1992 is reported to have been 35,000.[68] Bin Laden was one of the key players in organizing training camps for the foreign Muslim volunteers.[69][70]

The Soviet Union finally withdrew from Afghanistan in 1989. To the surprise of many, Mohammed Najibullah's communist Afghan government hung on for three more years, before being overrun by elements of the mujahideen. With mujahideen leaders unable to agree on a structure for governance, chaos ensued, with constantly reorganizing alliances fighting for control of ill-defined territories, leaving the country devastated.

Expanding operations

| “ | the correlation between the words and deeds of bin Laden, his lieutenants, and their allies was close to perfect—if they said they were going to do something, they were much more than likely to try to do it. Their record in this regard puts Western leaders to shame. | ” |

—Michael Scheuer, CIA Station Chief[71] | ||

Toward the end of the Soviet military mission in Afghanistan, some mujahideen wanted to expand their operations to include Islamist struggles in other parts of the world, such as Israel and Kashmir. A number of overlapping and interrelated organizations were formed, to further those aspirations.

One of these was the organization that would eventually be called al-Qaeda, formed by bin Laden with an initial meeting held on August 11, 1988.[72]

Notes of a meeting of bin Laden and others on August 20, 1988, indicate al-Qaeda was a formal group by that time: "basically an organized Islamic faction, its goal is to lift the word of God, to make His religion victorious." A list of requirements for membership itemized the following: listening ability, good manners, obedience, and making a pledge (bayat) to follow one's superiors.[73]

According to Wright, the group's real name wasn't used in public pronouncements because "its existence was still a closely held secret."[74] His research suggests that al-Qaeda was formed at an August 11, 1988, meeting between "several senior leaders" of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Abdullah Azzam, and bin Laden, where it was agreed to join bin Laden's money with the expertise of the Islamic Jihad organization and take up the jihadist cause elsewhere after the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan.[75]

Bin Laden wished to establish non-military operations in other parts of the world; Azzam, in contrast, wanted to remain focused on military campaigns. After Azzam was assassinated in 1989, the MAK split, with a significant number joining bin Laden's organization.

In November 1989, Ali Mohamed, a former special forces Sergeant stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, left military service and moved to California. He traveled to Afghanistan and Pakistan and became "deeply involved with bin Laden's plans."[76]

A year later, on November 8, 1990, the FBI raided the New Jersey home of Ali Mohammed's associate El Sayyid Nosair, discovering a great deal of evidence of terrorist plots, including plans to blow up New York City skyscrapers.[77] Nosair was eventually convicted in connection to the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, and for the murder of Rabbi Meir Kahane on November 5, 1990. In 1991, Ali Mohammed is said to have helped orchestrate bin Laden's relocation to Sudan.[78]

Gulf War and the start of U.S. enmity

Following the Soviet Union's withdrawal from Afghanistan in February 1989, bin Laden returned to Saudi Arabia. The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 had put the Kingdom and its ruling House of Saud at risk. The world's most valuable oil fields were within easy striking distance of Iraqi forces in Kuwait, and Saddam's call to pan-Arab/Islamism could potentially rally internal dissent.

In the face of a seemingly massive Iraqi military presence, Saudi Arabia's own forces were well armed but far outnumbered. Bin Laden offered the services of his mujahideen to King Fahdto protect Saudi Arabia from the Iraqi army. The Saudi monarch refused bin Laden's offer, opting instead to allow U.S. and allied forces to deploy troops into Saudi territory.[79]

The deployment angered Bin Laden, as he believed the presence of foreign troops in the "land of the two mosques" (Mecca and Medina) profaned sacred soil. After speaking publicly against the Saudi government for harboring American troops, he was banished and forced to live in exile in Sudan.

Sudan

From around 1992 to 1996, al-Qaeda and bin Laden based themselves in Sudan at the invitation of Islamist theoretician Hassan al Turabi. The move followed an Islamist coup d'état in Sudan, led by Colonel Omar al-Bashir, who professed a commitment to reordering Muslim political values. During this time, bin Laden assisted the Sudanese government, bought or set up various business enterprises, and established camps where insurgents trained.

A key turning point for bin Laden, further pitting him against the Sauds, occurred in 1993 when Saudi Arabia gave support for the Oslo Accords, which set a path for peace between Israeland Palestinians.[80]

Zawahiri and the EIJ, who served as the core of al-Qaeda but also engaged in separate operations against the Egyptian government, had bad luck in Sudan. In 1993, a young schoolgirl was killed in an unsuccessful EIJ attempt on the life of the Egyptian prime minister, Atef Sedki. Egyptian public opinion turned against Islamist bombings, and the police arrested 280 of al-Jihad's members and executed 6.[81]

Due to bin Laden's continuous verbal assault on King Fahd of Saudi Arabia, on 5 March 1994 Fahd sent an emissary to Sudan demanding bin Laden's passport; bin Laden's Saudi citizenship was also revoked. His family was persuaded to cut off his monthly stipend, $7 million ($10,400,000 in current dollar terms) a year, and his Saudi assets were frozen.[82][83] His family publicly disowned him. There is controversy over whether and to what extent he continued to garner support from members of his family and/or the Saudi government.[84]

In June 1995 an even more ill-fated attempt to assassinate Egyptian president Mubarak led to the expulsion of EIJ, and in May 1996, of bin Laden, by the Sudanese government.

According to Pakistani-American businessman Mansoor Ijaz, the Sudanese government offered the Clinton Administration numerous opportunities to arrest bin Laden. Those opportunities were met positively by Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, but spurned when Susan Rice and counter-terrorism czar Richard Clarke persuaded National Security AdvisorSandy Berger to overrule Albright. Ijaz’s claims appeared in numerous Op-Ed pieces, including one in the Los Angeles Times [85] and one in The Washington Post co-written with former Ambassador to Sudan Timothy Carney.[86] Similar allegations have been made by Vanity Fair contributing editor David Rose,[87] and Richard Miniter, author of Losing bin Laden, in a November 2003 interview with World.[88]

Several sources dispute Ijaz's claim, including the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks on the U.S. (the 9–11 Commission), which concluded in part:

Sudan's minister of defense, Fatih Erwa, has claimed that Sudan offered to hand Bin Ladin over to the U.S. The Commission has found no credible evidence that this was so. Ambassador Carney had instructions only to push the Sudanese to expel Bin Ladin. Ambassador Carney had no legal basis to ask for more from the Sudanese since, at the time, there was no indictment out-standing.[89]

Refuge in Afghanistan

After the Soviet withdrawal, Afghanistan was effectively ungoverned for seven years and plagued by constant infighting between former allies and various mujahideen groups.

Throughout the 1990s, a new force began to emerge. The origins of the Taliban (literally "students") lay in the children of Afghanistan, many of them orphaned by the war, and many of whom had been educated in the rapidly expanding network of Islamic schools (madrassas) either in Kandahar or in the refugee camps on the Afghan-Pakistani border.

According to Ahmed Rashid, five leaders of the Taliban were graduates of Darul Uloom Haqqania, a madrassa in the small town of Akora Khattak.[90] The town is situated near Peshawarin Pakistan, but largely attended by Afghan refugees.[90] This institution reflected Salafi beliefs in its teachings, and much of its funding came from private donations from wealthy Arabs. Bin Laden's contacts were still laundering most of these donations, using "unscrupulous" Islamic banks to transfer the money to an "array" of charities which serve as front groups for al-Qaeda, or transporting cash-filled suitcases straight into Pakistan.[91] Another four of the Taliban's leaders attended a similarly funded and influenced madrassa in Kandahar.

Many of the mujahideen who later joined the Taliban fought alongside Afghan warlord Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi's Harkat i Inqilabi group at the time of the Russian invasion. This group also enjoyed the loyalty of most Afghan Arab fighters.

The continuing internecine strife between various factions, and accompanying lawlessness following the Soviet withdrawal, enabled the growing and well-disciplined Taliban to expand their control over territory in Afghanistan, and it came to establish an enclave which it called the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. In 1994, it captured the regional center of Kandahar, and after making rapid territorial gains thereafter, conquered the capital city Kabul in September 1996.

After the Sudanese made it clear, in May 1996, that bin Laden would never be welcome to return,[clarification needed] Taliban-controlled Afghanistan—with previously established connections between the groups, administered with a shared militancy,[92] and largely isolated from American political influence and military power—provided a perfect location for al-Qaeda to relocate its headquarters. Al-Qaeda enjoyed the Taliban's protection and a measure of legitimacy as part of their Ministry of Defense, although only Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan.

By the end of 2008, some sources reported that the Taliban had severed any remaining ties with al-Qaeda,[93] while others cast doubt on this.[94] According to senior U.S. military intelligence officials, there were fewer than 100 members of Al-Qaeda remaining in Afghanistan in 2009.[95]

Call for global jihad

| This section requires expansion. |

Around 1994, the Salafi groups waging jihad in Bosnia entered into a seemingly irreversible decline. As they grew less and less aggressive, groups such as EIJ began to drift away from the Salafi cause in Europe. Al-Qaeda decided to step in and assumed control of around 80% of the terrorist cells in Bosnia in late 1995.

At the same time, al-Qaeda ideologues instructed the network's recruiters to look for Jihadi international, Muslims who believed that jihad must be fought on a global level. The concept of a "global Salafi jihad" had been around since at least the early 1980s. Several groups had formed for the explicit purpose of driving non-Muslims out of every Muslim land, at the same time, and with maximum carnage. This was, however, a fundamentally defensive strategy[clarification needed].

Al-Qaeda sought to open the "offensive phase" of the global Salafi jihad.[96] Bosnian Islamists in 2006 called for "solidarity with Islamic causes around the world", supporting the insurgents in Kashmir and Iraq as well as the groups fighting for a Palestinian state.[97]

Fatwas

In 1996, al-Qaeda announced its jihad to expel foreign troops and interests from what they considered Islamic lands. Bin Laden issued a fatwa(binding religious edict),[98] which amounted to a public declaration of war against the U.S. and its allies, and began to refocus al-Qaeda's resources on large-scale, propagandist strikes. In June 1996, the Khobar Towers bombing took place in Khobar, Saudi Arabia, attributed by some to al-Qaeda, killing 19 and wounding 372.[99]

On February 23, 1998, bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, a leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, along with three other Islamist leaders, co-signed and issued a fatwa calling on Muslims to kill Americans and their allies where they can, when they can.[100] Under the banner of the World Islamic Front for Combat Against the Jews and Crusaders, they declared:

[T]he ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, in order to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque [in Jerusalem] and the holy mosque [in Mecca] from their grip, and in order for their armies to move out of all the lands of Islam, defeated and unable to threaten any Muslim. This is in accordance with the words of Almighty Allah, 'and fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together,' and 'fight them until there is no more tumult or oppression, and there prevail justice and faith in Allah'.[101]

Neither bin Laden nor al-Zawahiri possessed the traditional Islamic scholarly qualifications to issue a fatwa. However, they rejected the authority of the contemporary ulema (which they saw as the paid servants of jahiliyya rulers), and took it upon themselves.[102][unreliable source?] Former Russian FSB agent Alexander Litvinenko, who was later killed, said that the FSB trained al-Zawahiri in a camp in Dagestan eight months before the 1998 fatwa.[103][104]

In Iraq

Al-Qaeda is Sunni, and often attacked the Iraqi Shia majority in an attempt to incite sectarian violence and greater chaos in the country.[105] Al-Zarqawi purportedly declared an all-out war on Shiites[106] while claiming responsibility for Shiite mosque bombings.[107] The same month, a statement claiming to be by AQI rejected as "fake" a letter allegedly written by al-Zawahiri, in which he appears to question the insurgents' tactic of indiscriminately attacking Shiites in Iraq.[108] In a December 2007 video, al-Zawahiri defended the Islamic State in Iraq, but distanced himself from the attacks against civilians committed by "hypocrites and traitors existing among the ranks".[109]

U.S. and Iraqi officials accused AQI of trying to slide Iraq into a full-scale civil war between Iraq's majority Shiites and minority Sunni Arabs, with an orchestrated campaign of civilian massacres and a number of provocative attacks against high-profile religious targets.[110] With attacks such as the 2003 Imam Ali Mosque bombing, the 2004 Day of Ashura and Karbala and Najaf bombings, the 2006 first al-Askari Mosque bombing in Samarra, the deadly single-day series of bombings in which at least 215 people were killed in Baghdad's Shiite district ofSadr City, and the second al-Askari bombing in 2007, they provoked Shiite militias to unleash a wave of retaliatory attacks, resulting in death squad-style killings and spiraling further sectarian violence which escalated in 2006 and brought Iraq to the brink of violent anarchy in 2007.[111] In 2008, sectarian bombings blamed on al-Qaeda killed at least 42 people at theImam Husayn Shrine in Karbala in March, and at least 51 people at a bus stop in Baghdad in June.

Somalia and Yemen

The percentage of terrorist attacks in the West originating from the Afghanistan-Pakistan (AfPak) border declined considerably from almost 100% to 75% in 2007, and to 50% in 2010, as Al-Qaeda shifted to Somalia and Yemen.[112] While Al-Qaeda leaders are hiding in the tribal areas along the AfPak border, the middle-tier of the movement display heightened activity in Somalia and Yemen. “We know that South Asia is no longer their primary base,” a U.S. defense agency source said. “They are looking for a hide-out in other parts of the world, and continue to expand their organization.“

In Somalia, Al-Qaeda agents closely collaborate with the Shahab group, actively recruit children for suicide-bomber training, and export young people to participate in military actions against Americans at the AfPak border. In January 2009, Al-Qaeda’s division in Saudi Arabia merged with its Yemeni wing to form Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[113] Centered in Yemen, the group takes advantage of the country's poor economy, demography and domestic security. In August 2009, they made the first assassination attempt against a member of the Saudi royal dynasty in decades. President Obama asked his Yemen counterpart Ali Abdullah Saleh to ensure closer cooperation with the U.S. in the struggle against the growing activity of Al-Qaeda in Yemen, and promised to send additional aid. Because of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. is unable to pay sufficient attention to Somalia and Yemen, which may cause the U.S. some serious problems in the near future.[114] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed responsibility for the 2009 bombing attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253 by Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab.[115] The group released photos of Abdulmutallab smiling in a white shirt and white Islamic skullcap, with the Al-Qaeda in Arabian Peninsula banner in the background.

American operations

In December 1998, the Director of Central Intelligence Counterterrorist Center reported to the president that al-Qaeda was preparing for attacks in the USA, including the training of personnel to hijack aircraft.[116]

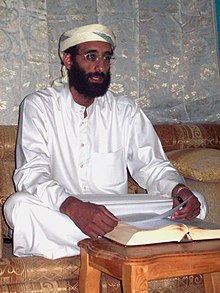

U.S. officials called Awlaki an "example of al-Qaeda reach into" the U.S. in 2008 after probes into his ties to the September 11 hijackers. A former FBI agent identifies Awlaki as a known "senior recruiter for al-Qaeda", and a spiritual motivator.[117] Awlaki's sermons in the U.S. were attended by three of the 9/11 hijackers, as well as accused Fort Hood shooter Nidal Malik Hasan. U.S. intelligence intercepted emails from Hasan to Awlaki between December 2008 and early 2009. On his website, Awlaki has praised Hasan's actions in the Fort Hood shooting.[118]

An unnamed official claimed there was good reason to believe Awlaki "has been involved in very serious terrorist activities since leaving the U.S. [after 9/11], including plotting attacks against America and our allies.”[119] In addition, "Christmas Day bomber" Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab said al-Awlaki was one of his al-Qaeda trainers, meeting with him and involved in planning or preparing the attack, and provided religious justification for it, according to unnamed U.S. intelligence officials.[120][121][122] In March 2010, al‑Awlaki said in a videotape delivered to CNN that jihad against America was binding upon himself and every other able Muslim.[123][124]

U.S. President Barack Obama approved the targeted killing of al-Awlaki by April 2010, making al-Awlaki the first U.S. citizen ever placed on the CIA target list. That required the consent of the U.S. National Security Council, and officials said it was appropriate for an individual who posed an imminent danger to national security.[125][126][127][128] In May 2010, Faisal Shahzad, who pleaded guilty to the 2010 Times Square car bombing attempt, told interrogators he was "inspired by" al-Awlaki, and sources said Shahzad had made contact with al-Awlaki over the internet.[129][130][131] Representative Jane Harman called him "terrorist number one", and Investor's Business Daily called him "the world's most dangerous man".[132][133] In July 2010, the U.S. Treasury Department added him to its list of Specially Designated Global Terrorists, and the UN added him to its list of individuals associated with al-Qaeda.[134] In August 2010, al-Awlaki's father initiated a lawsuit against the U.S. government with the ACLU, challenging its order to kill al-Awlaki.[135] In October 2010, U.S. and U.K. officials linked al-Awlaki to the 2010 cargo plane bomb plot.[136]

No comments:

Post a Comment